Some of you may recognize the name Murray “Slim” Gordon Lewis from his long and storied career as a musician in Ontario and across North America. For others, like the editor’s parents, he was your insurance salesman.

Some of you may recognize the name Murray “Slim” Gordon Lewis from his long and storied career as a musician in Ontario and across North America. For others, like the editor’s parents, he was your insurance salesman.

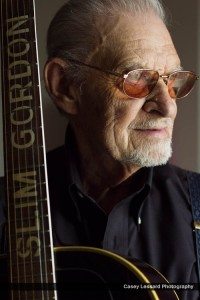

Slim Gordon, as he was called, was born in 1926 in Yarmouth County, Nova Scotia. Today, he lives alone in an apartment in Exeter. In December, he was diagnosed with cancer. A fellow reader, Diane Lovie thought you might like to hear his story.

As told to Casey Lessard

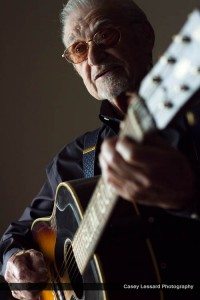

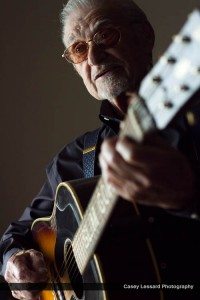

Portraits by Casey Lessard

WSM images courtesy Slim Gordon

I had my own radio program when I was six years old in Yarmouth, Nova Scotia. I had been performing with other kids on a children’s program every Saturday afternoon, and the Rawleigh man came to the house one day. He was so used to our place that he just walked in. My mother played the pump organ and she was teaching me a new song I was going to learn for the program on Saturday. When we were done, my brother came into the parlour room to tell us that he was out there, so we went into the kitchen. He had been listening to the rehearsal.

I was a boy soprano and he said to my mother, “The radio station is looking for someone to star in a program, and my wife plays piano for them.” He said, “Why don’t you bring your son down some evening and let my wife hear him?” She took me down and I got the program.

I did that for two years. The announcer was also the announcer for the show with the children. He retired to Newfoundland, so they didn’t have an announcer to do the kid’s shows. He was very good at it. I remember they didn’t have an adjustable microphone. It was a set height. If they stood me on a chair, I was too tall. If they didn’t stand me on a chair, I was too short. They had to sit me on the announcer’s lap to do the program. He was adjustable.

Boston-bound

When I was 15, I decided to start my own band. I rented a country hall for $5 per night, and we made our own posters. We had a full house. We charged 25 cents admission, and made $7 each. Farmer’s helpers were working a whole month for $10.

This was 1941. We didn’t have electric instruments. Everything was acoustic. It was a rousing success.

When I was 17, we had a dairy farm and a milk route and delivered milk by the bottle. I met a customer one Sunday, and his wife told him I sang cowboy music. There was no such thing as country music at the time. John lived in Boston, Massachusetts. He said I ought to go to the radio station and get a program on the radio.

I stayed with my uncle, who lived in Boston. While there, John took me to a country outfitters. My father gave me $100 to buy western pants, a western shirt, belt and boots, and a new guitar. John took me to a photographer and I had my picture taken. He took my picture around to the different nightclubs and tried to book me. Damned if he didn’t! I played a different nightclub every night. I was 17 and too young to drink, but that didn’t matter.

He took me to WMEX radio, and a fellow named Gene LaVerne had a country band and did a country show every day at noon. He listened to me sing and told me he didn’t have any work for me, but he got me some bookings.

John got me booked on the Boston Barn Dance, which was broadcast from the Armories every Wednesday night. I did one show and then the next week. We were leaving to come back to the house, and there were three girls standing in the lobby.

One girl came over, shook my hand, and said her name was Betty Lee. “I’m going to be doing a tour of Nova Scotia,” she said. “We’re going to be doing a radio show there and we’re looking for a boy who can sing, play guitar and act as straight man for our comedian.”

How much do you pay?, I asked. “You get $25 a week, even if you don’t work the whole six days. And you won’t have to worry about the fare back to Yarmouth because we have our own car.” So I had a job.

The next year, she was planning a U.S. tour, but I couldn’t get a work permit to work in the U.S. because they were still under wartime rules. The company I was working for offered me a position in Hamilton, and I took the chance. I worked for Cosmos Imperial Mills and I ran a loom that wove felt that was 40’ wide by 200’. It was used in paper mills.

The move to Ontario

The move to Ontario

I came to Hamilton in 1948 and started my band in 1949. We were doing a Saturday night show with three other bands at CKPC radio in Brantford. The Cockshutt plow company was hosting a show and they wanted a country band. The plowing match was coming up in Paris, and the announcer thought it would be fair to run a contest for the four bands to do the job. The audience chose. We got the job.

We had sporadic work. We rehearsed in case something came up. Then the band started pestering me. “We’ve been rehearsing two to three nights a week for two years. Are we ever going to go out and get jobs working nightclubs or something?” So I thought, well, we have a big enough repertoire – I could do 500 songs myself – maybe I should go see what I can do.

We had an audition at Hanrahan’s Tavern, and we got our first job. I told him what our price was and he accepted it. We didn’t have an argument. We had a two-week gig, which was normal. The first week, I noticed a guy came in and sat at the bar. He looked like a businessman. He came again the next night. He said, “I’m Harold Kudlutz, I book bands.” He became our agent. He booked us for quite a long time.

I had a good paying job because not a lot of people can weave felt. Now I had a problem. Halfway through the second week at Hanrahan’s, I was bushed. I went to my factory manager and explained the situation. I asked for Wednesday mornings off to get a day that I could sleep in and catch up. I didn’t want to quit what I was doing because I had been working toward it for a long time. He agreed to it.

Then, by golly, we started getting bookings in Toronto. So I went back to him. “Now what do you need,” he says. “Well,” I told him, “I’ll make it short and to the point. Can I get a six-month leave of absence?” It’s quite a question to ask someone. He said, “I suppose if I don’t give it to you, you’re going to quit.” I told him, “I guess you’re right.” He gave it to me.

That was the end of working in a factory. I never went back.

By this point, I had been married a long time. Since 1950. We met when I was trying to start a show in Hamilton at a supper club with a dance floor. I was hoping it would be a success, but it bombed. We ran it for four nights. My best friend was putting up the money for it, and he wasn’t a rich man.

Rita Muir was a girlfriend of my competitor, Mike Patoma. He came to one of the shows, and brought her and her girlfriend.

He took me down and introduced me to her. It was a mistake on his part, if he was serious. But then, it was a big mistake on my part because I married her. We were married for 12 years. Twelve years of pure hell. We had three daughters, but the last one, Leslie, wasn’t mine. That was the end of the marriage.

That didn’t stop me from loving the little girl. She had nothing to do with it. When we broke up, Rita took Leslie with her.

Last January, one of my daughters died of cancer. The night of her memorial, some of the family came and Leslie came, too. I said, “The last time I saw you, you were 10 years old.”

She said, “I remember the last time I saw you.” I asked how old she was, and she said 52. I said, “I haven’t seen you for 40 years.” She looked the same. I couldn’t believe it. Forty years. And she still felt like my daughter. She threw her arms around my neck and stood there and cried. It had to be 20 minutes. I haven’t seen her since.

Hit the road, Slim

(After my marriage ended,) I did a tour with George Jones and one with Hank Snow, each for a month. I’m still playing nightclubs, but now I play Toronto a lot. We didn’t have a holiday for two years, so I went back to Oshawa, where I bought a house. I gave Rita the house in Hamilton to take care of the girls.

I used to run Saturday night shows in the Red Barn. In the fall of ’64, a fellow came who owned a dude ranch north of Kirkland Lake. He wanted to know whether the band and I would do a TV show from the ranch as a form of advertising. We settled on a price for Sunday night.

The guy was going to try to pull a fast one on me. If you’re in this business long enough, you get wise to this stuff. He wrote me a cheque that night when the show was finished. I was up the next morning when the bank opened and I went into the bank. The teller told me they couldn’t honour any more cheques from him. I could see his idea of the TV show, but not with my money. Back to the ranch.

I pull into the yard of the ranch, and he’d just come out of the ranch house with a metal cash box in his hand, heading for the bank. He said, “Where’ve you been?” I said, “To the bank, they wouldn’t honour your cheque.” He told me to come back into the ranch house and he’d give me cash. All smiles, I told him that would suit me just dandy. His wife stood there gritting her teeth.

We wound up in Hearst, the last jumping off point in Ontario. You either have to turn east or west; you can’t go north, no highway. I met a guy who came and asked if he could play banjo on my show. His name was Smiley Bates. Not too many guys running around playing the five-string banjo. Hard to play.

He said, “I play everything. If it’s got strings on it, I play it.” And he did. He played them all equally well. I needed a smaller band to play nightclubs, so I thought I’d hire him. Before I left Hearst, I had a booking at the Franklin Hotel in Kirkland Lake.

I had two weeks off and I was in Oshawa. My agent called and said the band playing the Queen’s Hotel in Seaforth was from the United States and their banjo player ruptured his appendix. They can’t play a show without him. He asked if we would fill in. And here I thought we’d have two weeks off.

We had a ball. The second night we were there, Smiley said to me, “Did you see the blonde that came in here?” I said, “I’m not bothered with women, I just came through a bad marriage.” He said, “She’s really something. She’s got blonde hair she can sit on.” And she did. I like long hair.

He said he’d take me down and introduce me during the break. That was his mistake. I sat and talked to her until my break was over. She had a good head, and she was real pretty. Her name was Lydia Roelofs. Dutch. She was a dandy.

When we got married, she was 20 and I was 40. They told me I was robbing the cradle. We were married for 34 years. Had two kids that made us proud. Their mother, I give the credit for that because I was on the road all the time.

I took three weeks off, and thought, I can’t subject Lydia to life on the road. If I take her to Oshawa and dump her in my apartment, I don’t know when I’m going to get back and that wouldn’t be fair to her. I thought if she could stay in Exeter, that would work out because she has friends here, went to high school here.

End of the line

In 1970, I got booked in Vietnam, so I took it. The money was damn good. I was going to be entertaining American troops.

It was busy. You flew somewhere every day of the week. If you couldn’t fly, you took a train or a van. I was by myself, no road band. A lot of clubs had house bands. You want to talk about bands? Get a Japanese or Filipino country band; as good as anything in Nashville. Couldn’t speak a word of English. Well, there was always one guy who could speak enough that you could get by, but other than that, no. Did that for 17 weeks.

The closest I came to being in danger that I know of, I was flying from Manila in the Philippines to Taipei, Taiwan. When we got there, my road manager came running as I came down the gangplank. He said, “We were really worried. We didn’t know if you were going to get here or not.” I said, why?

He said, “What time did you leave Manila?” Quarter past twelve. He said, “Well, they blew up the airport at 12:30.”

I was over there in 1970 over Christmas, New Year’s, and my birthday, December 30. I missed my family, and I thought this is a stupid damn job. I’m 10,000 miles away from my family at Christmastime. I should start doing something else. I don’t think I’m ever going to be a big star. Just a little star. This is after 31 years in the business.

I came home and didn’t do anything for a month. I told my wife I wasn’t going to do anything for a year. I was going back to college for woodworking. I’ve always loved woodworking all my life. I took a course in fine carpentry and cabinet making. I loved it. Made loads of stuff.

I built my own house. I knew how to do that because we did it at school. I worked in insurance for 18 years until I retired. I lived in that house for 25 years.

A sudden change

In 1999, Lydia died. Heart stopped. She hadn’t been sick. Doctor didn’t know there was anything wrong with her.

It was two days before Christmas. Twenty-third of December. She was laying out her pies because we were going to have both of the children with their families. She said to me, “When you have your sandwich, could you go uptown and get the Christmas turkey?” Holtzmann’s had called and told us our fresh turkey had arrived from Hayter’s.

It was 2:20 because I looked at my watch. I went uptown, got the turkey, came back home, and my wife was dead on the floor. That’s all the warning we had. The end of a happy marriage.

I couldn’t believe it. It was days before I could think it wasn’t happening. A bad dream; I couldn’t wake up.

Phoned the kids and told them. Thursday. Thursday afternoon. Couldn’t believe it. Thought I was safe. I’m going to die first, for sure, because there’s 20 years between us.

I lived eight years in the house by myself. I was lonely there. The house had everything we wanted. Took me six and a half years to build it because I was working in the insurance office. All beams in the ceiling. A huge backyard. Four thousand square feet. Five bedrooms, pool room, a bar with more booze than some of the clubs I played in. But it became too much for me.

I never thought I’d wind up like this (living in an apartment). I thought my wife and I would live in our house.

A new battle

In December, I wasn’t feeling that well. I had trouble with my throat, and I went to the doctor. They decided to run some tests.

First, they did an ultrasound. Then they found something. They did an x-ray and a CAT scan. The CAT scan nailed it down. She said, “You’ve got cancer.” In my kidney.

I thought, you can haul one out and leave the other one.

I went to the surgeon in London, Dr. Chin. He’s the top surgeon in London. I told him I’m a Jehovah’s Witness, so I don’t take blood. He said, “Just a moment. You don’t have to worry about the blood because I’m not going to operate. You’re 83 years old. Most people don’t realize how complex a kidney operation is. It’s a hell of a shock to your system. I think the shock would kill you.” Shit.

So here I sit. I’m looking at alternative medicine. Conventional medicine won’t look at that at all. It’s a hell of an attitude. They’re killing people doing that.

It’s a pain in the ass, no, the kidney. When it comes to alternative health, you can control it through what you eat. The guy I’m dealing with now is Dr. Julian Whittaker in California. He’s been using this system for 30 years and never had a failure yet. I could be number one.

I’m not cryin’. I’m a Jehovah’s Witness. I’m not afraid of dying anymore. I was apprehensive before, but I’m not afraid now. There’s no such thing as hell.

I’ve got nothing to complain about. I’m happy I lived in the time that I lived. From 1926 to 2010, that’s a hell of a long time. Look at the changes I’ve seen. I think I’m pretty lucky.

Pinnacle of a career

Pinnacle of a career

In 1962, I was running shows at the Red Barn in Oshawa Sunday nights in the wintertime. I was bringing in talent from Nashville and Wheeling; both had 50,000-Watt stations. I had booked Skeeter Davis, who had about five gold hits by then. She was going to be flying in Saturday evening. I couldn’t go pick her up because I was doing the radio show, so I sent my wife down to pick her up at the airport. She brought her up to the station, so she was there when I signed off. I had written and rewritten the signoff about five or six times. “Mama, put the kettle on, I’m coming home.” Thanked the people for listening. Skeeter is listening to this, and when I got finished, I looked at her and she had tears in her eyes. She said, “That’s the most beautiful close I’d ever heard. Could you do that again on a tape not going out on the air?” I did it.

She took it home to Ralph, her husband, an all-night DJ at WSM Nashville. She played it for the board of directors. They said, that’s our next DJ.

I got a telegram from WSM at the end of October asking me to come to Nashville September 2, 1962. Nashville voted me Mr. DJ USA. I’m the only Canadian that ever got that award. I did a one-hour broadcast as a DJ from Nashville. We had five or six Opry stars lined up for my show.

Later, I walked out on the stage to perform at the Grand Ole Opry. In the floor of the stage at the Grand Ole Opry, there’s a circle there about 8’ to 10’ in diameter, where it’s new wood. That’s where all the stars perform because that’s centre stage. Walking out there, when you see that circle and you know you’re going to stand there, it gives me teardrops. You feel about two inches high. Really humble. I did a song, “I’ll Pretend There Was No Yesterday”.

That was the pinnacle.